Unable to see past the war and instability engulfing the rest of the Middle East, many will look at you with sceptical concern when you inform them that you are going to Oman. Images of suicide bombings in Iraq, Lebanon’s sprawling refugee camps and Yemeni children holding AK-47s inevitably infiltrate perceptions of the region. But this beautiful, quiet and stable corner of the Arabian Peninsula could not be further from the visions of conflict that dominate the mainstream media.

Rooftop view of Muscat (image: author’s own)

Rooftop view of Muscat (image: author’s own)

Thanks to its historic trade links with East Africa, its brief encounter with Portuguese colonialism and the waves of migration crossing the Arabian Peninsula, Oman plays host to various ethnicities and languages. Omani families of Zanzibari origin speak Swahili at home, while others are descended from the Southern Pakistani Baluchi tribes. However, none of these groups feel any less Omani than their ethnically Arab counterparts.

The official religion is Islam and the majority of the people belong to the Ibadi sect, which emphasises the importance of respect and tolerance of other religions. This is arguably the reason why Oman remains one of the only peaceful countries in the region, and what Vanity Fair calls ‘the Middle East’s most welcoming absolute monarchy’.

The Sultan Qaboos Grand Mosque (image: Rough Guides)

The Sultan Qaboos Grand Mosque (image: Rough Guides)

Geographically, however, Oman is much more dramatic: white beaches, towering mountains and vast empty deserts make it the perfect destination for intrepid nomads and luxury travellers alike.

But the time to visit is now. Heavy investment in the tourism industry means this undiscovered haven is quickly being discovered, and with its discovery will come vast numbers of mid-range hotels, hoards of holidaymakers, and the gradual dilution of Oman’s unique and rich culture. Whilst Oman has so far managed to avoid such commercialisation of the likes of Dubai, dwindling oil reserves will leave few other options for economic growth as diversification becomes increasingly necessary.

Wadi Shab (image: amazingplacesonearth.com)

Wadi Shab (image: amazingplacesonearth.com)

In March this year Sultan Qaboos al Said bin Said returned from Germany, where he had been in hospital since July 2014. While official sources have not commented on the Sultan’s health, rumours in Oman have suggested that the Sultan has been receiving treatment for cancer, meaning that the country will soon have to face one of the most pressing concerns in its recent history: the issue of succession.

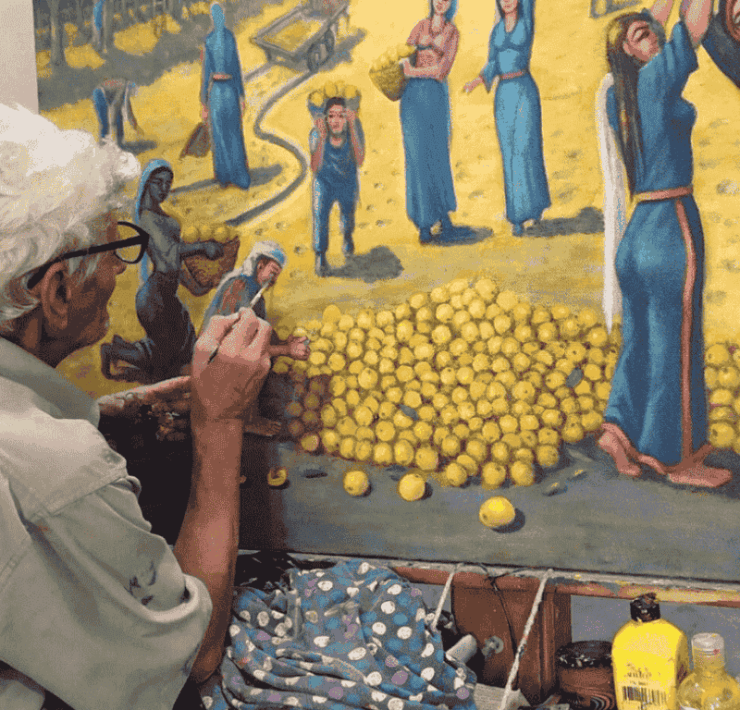

In 1970, Qaboos overthrew his father in a British-backed coup and embarked upon a drastic process of modernisation and development in the Sultanate. Many areas previously had no electricity and little or no access to public services such as education or healthcare – Oman had just two hospitals and six miles of paved road. But over the last forty years, Qaboos has used income from Oman’s oil reserves to transform the country. This has resulted in the building of schools and hospitals, improved infrastructure and the creation of a budding tourism industry, all the while maintaining the country’s unique and enchanting heritage in a way that other Gulf monarchies have failed to do. Qaboos has also acted as one of the West’s most valuable allies in the region, mediating the early stages of the nuclear agreement that has just been reached between Iran and the P5+1. He has acted as the country’s head of state, prime minister, defence minister, and finance minister – but eventually the country will have to face the inevitable reality of a future without him.

The Wahiba desert in Sharqiya (image: author’s own)

The Wahiba desert in Sharqiya (image: author’s own)

What does this mean for his people, who love him like a father? And for his Western allies, who need the stability of a country like Oman now more than ever? The Sultan has no obvious successor as he has no brothers and has never had any children of his own. According to the constitution, in the event of his death, the ruling family has three days to choose a successor,- and if they cannot decide then they are to open an envelope containing Qaboos’s recommendation, which has been kept secret.

However, there are a number of problems that could arise from this scenario. Firstly, if the ruling family decide on a successor before the three day cut-off mark, this successor runs the risk of losing favour with the people if he tries to make changes to the system that Qaboos built from scratch. Omanis love and trust Qaboos like a father, which would automatically give his chosen successor a legitimacy that somebody chosen by the ruling family would not have.

If the ruling family fail to agree, some worry that possible infighting within the family could divide and destabilise the country. Others are concerned that old conflicts could re-surface, such as the insurgency in the Dhofar region that Qaboos, with the help of the British, managed to quell upon succeeding his father.

On an international level, there are concerns about what this could mean for the West’s position in an already volatile region. Qaboos’s foreign policy has been favourable to Britain and the US, but without alienating potential threats to the West such as Iran. A deviation from this could deprive the west of a strategically-positioned, moderate ally in a region that is becoming ever more dangerous and intolerant of western interference. Further to this, some worry that a proxy conflict over succession could ensue between neighbouring Saudi Arabia and Iran, which could destabilise the newly reached nuclear deal and exacerbate the sectarian conflict that is ensuing in other parts of the region.

Sultan Qaboos and Queen Elizabeth (image: zimbio.com)

Sultan Qaboos and Queen Elizabeth (image: zimbio.com)

The future of this unique country in the corner of the Arabian Peninsula is far from certain, but what is clear is that Omanis will not lose their extraordinary pride of their nation or their hopes for its bright future. And finally, that there will surely never be a ruler in Oman, or probably anywhere else, as loved and respected as Sultan Qaboos.