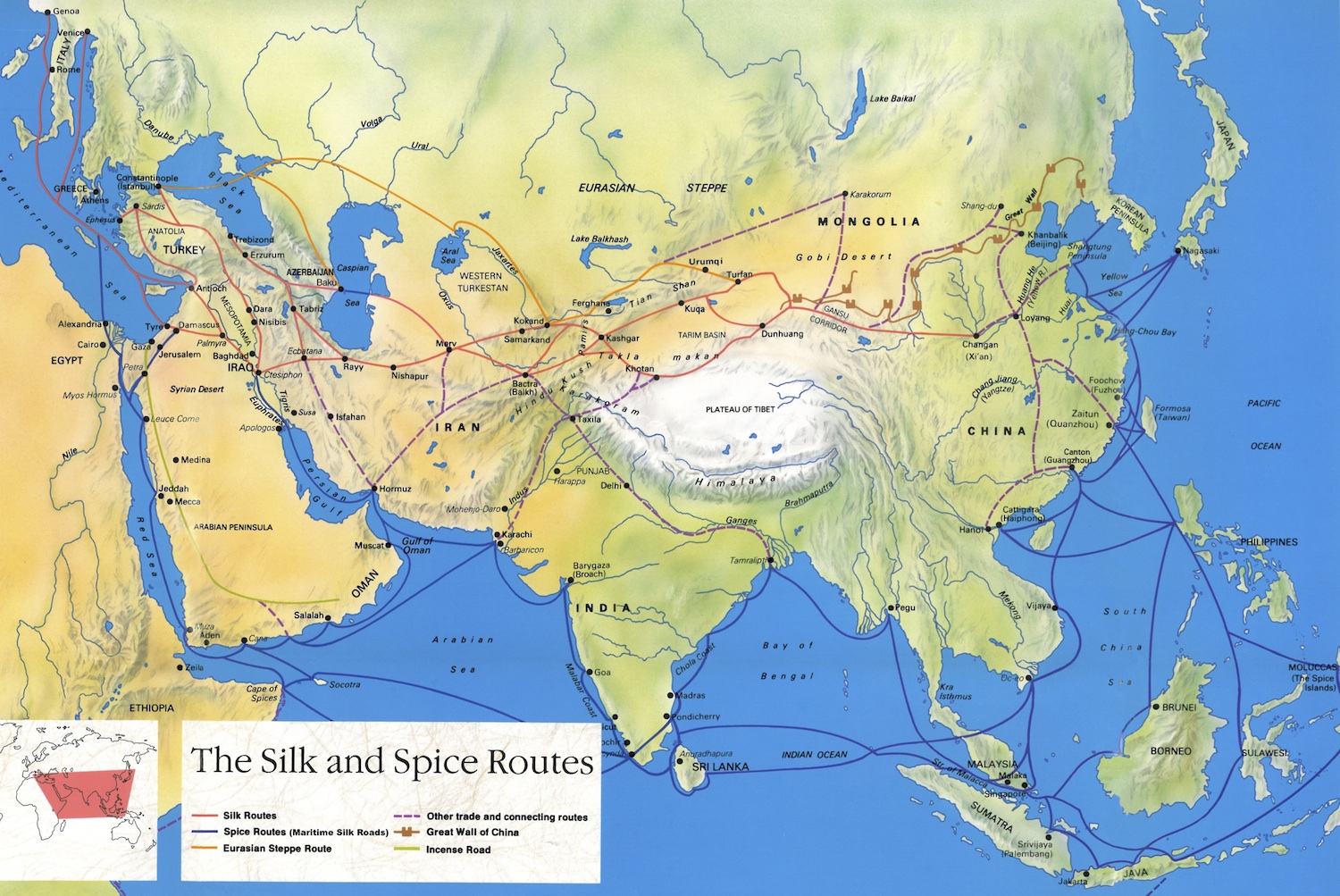

If you read one book this year, it should be Peter Frankopan’s The Silk Roads: A New History of the World. His captivating exploration of the historic interactions between empires, countries and cultures follows the routes of the ancient Silk Roads, which served to link the Mediterranean in the west to China in the east. The Silk Roads traces the exchange of goods, currencies, ideas and religions along these ancient pathways, but also the flow of conflict, slavery and disease.

Dr Peter Frankopan, a historian at Oxford University, fundamentally challenges the version of history we have been taught, which emphasises the political dominance and enlightenment of the west. In fact, Frankopan argues, “for millennia, it was the region lying between east and west, linking Europe with the Pacific Ocean, that was the axis on which the globe spun”.

Dr Peter Frankopan, a historian at Oxford University, fundamentally challenges the version of history we have been taught, which emphasises the political dominance and enlightenment of the west. In fact, Frankopan argues, “for millennia, it was the region lying between east and west, linking Europe with the Pacific Ocean, that was the axis on which the globe spun”.

His account lays out the historical context of the conflicts and complexities that have come to characterise the Middle East and parts of Central Asia, demonstrating that the challenges the world faces today are firmly rooted in history. Frankopan presents us with a stark reminder that history is written by the victor and that the best way to navigate the future is by looking to the past.

Though at times a bit of a tough read due to the depth of the content, The Silk Roads is an absolute must-read, whether you’re a self-confessed history nerd, a student of the region or just someone trying to make meaningful sense of what’s going on in the Middle East. On top of the impressive historical detail, it sheds light on a number of issues that today are frequently the subject of bias and finger-pointing, including religious conflict, slavery and the brutality of empire.

For example, in a chapter entitled ‘The Road of Faiths’, Frankopan describes how virtually every major religion has been exploited for personal economic and political gain. He explains how the leaders of the ancient world would change their own religion and that of their subjects at the drop of a hat to forge political and trading links with other dominant powers. He also deconstructs the political and economic motivations behind historical wars fought in the name of religion including the Crusades, encouraging the reader to think more critically about the religious conflicts of today.

Another interesting chapter is ‘The Slave Road’, which charts the early history of the global trade in human beings – arguably one of the world’s oldest currencies. Frankopan emphasises the prolific trafficking of the Slavic peoples, who were transported south by the Vikings of Scandinavia to be traded in markets from Afghanistan to Spain. Northern and western Europeans were also trafficked by Muslim traders to be sold at the markets of the Mediterranean. The trading of African slaves in Western Europe and the Americas can therefore be seen as the continuation of a long and well-practised tradition of human trafficking.

Caravans travelled the routes of the Silk Roads trading goods, people and ideas (image: China Culture Tour)

Caravans travelled the routes of the Silk Roads trading goods, people and ideas (image: China Culture Tour)

An overriding theme of The Silk Roads appears to be the brutality of the age-old practice of colonialism and empire. The book charts the struggle for dominance between armies, nations, races and religions, offering a fascinating if slightly depressing insight into human nature. It shows how, for centuries, human beings have exploited one another for their own interests, culminating in a blunt account of the hypocritical and damaging policies pursued by the US in the 20th century in their attempts to achieve control over the natural resources of the Middle East.

The book ends by presenting the compelling and thought-provoking conclusion that the era of the west is over and we are witnessing the emergence of a new world order. It cites the rising influence of the countries of the east, which are increasingly cooperating politically and investing financially in one another, showing how money and ideas are once again flowing along the old Silk Roads.