One of the greatest obstacles standing in the way of the pursuit of gender equality in the Middle East is the continued practice of female genital mutilation (FGM) in many regional countries.

The World Health Organisation estimates that more than 200 million girls and women alive today have undergone FGM across 30 countries, and that an additional 3 million girls are at risk of undergoing the practice every year.

Many people believe that FGM only occurs in Africa, however it is also prevalent in various Middle Eastern societies, where it is particularly difficult to address because of the conservative culture and the taboo surrounding the issue.

FGM is practiced by communities of various religions, including Muslim communities. Despite the fact that it predates Islam and is not mentioned in the Quran, the practice is often linked with religion by those who seek to justify it.

In the societies where it takes place, FGM is justified as a means of keeping women from losing their virginity, keeping them “clean”, and reducing a woman’s sexual pleasure and desire, therefore lessening the likelihood of extramarital sex and “deviant” behaviour. The practice can cause serious health problems including infection, chronic pain, infertility, haemorrhaging, cysts and difficult labour.

Religion is often used to justify FGM in the areas where it takes place (image: The Islamic Monthly)

Religion is often used to justify FGM in the areas where it takes place (image: The Islamic Monthly)

Challenges of addressing FGM in the Middle East

Lack of data

One of the biggest challenges facing those fighting FGM in the Middle East is the lack of available data on where, and how prolifically it takes place. The UN only recognised that FGM was an issue in the Middle East in 2016, so there was little pressure on regional governments to fully understand and tackle the issue before then.

The restrictions placed on NGOs working in the region – particularly those working on sensitive issues such as this – also makes it difficult to collect data and reach victims.

The stigma surrounding FGM

The practice tends to take place in very conservative societies, where raising awareness of the health risks can be very difficult as the subject is considered taboo and very few women are prepared to talk openly about their experiences.

Roots in local culture

The fact that FGM is often deeply rooted in local culture poses another challenge for those working to halt the practice. This is particularly the case in more conservative, rural areas, where emphasis on tradition has sustained gender inequality. In these situations, women are viewed as the gatekeepers of family honour – which can determine social standing. So it is often believed that girls’ sexual desires must be controlled early on to preserve virginity and prevent immorality.

Religious justification

As well as being a cultural norm in some societies, FGM is also believed by many to be compulsory under Islam. As mentioned above, there is no mention of FGM in the Quran and it has been practiced since before the birth of Islam. However, a number of influential clerics and religious authorities in the region continue to justify it.

Artwork from an Amnesty International campaign to end FGM (image: MSNBC)

Artwork from an Amnesty International campaign to end FGM (image: MSNBC)

What is the solution?

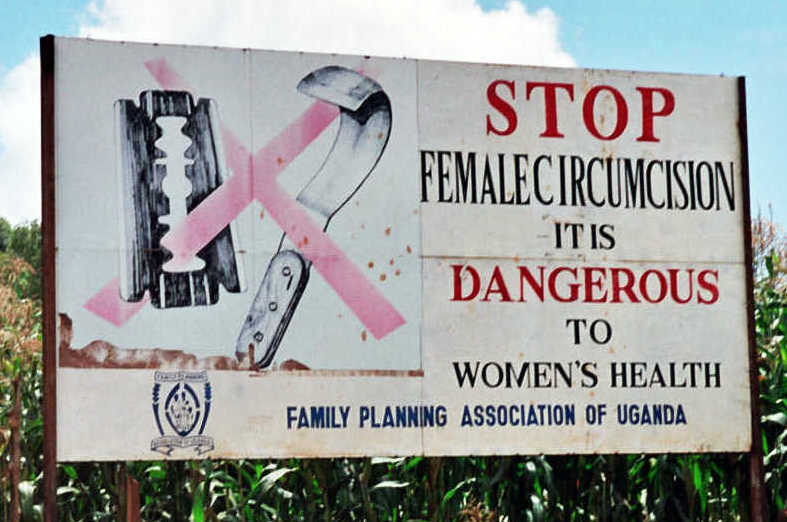

Various steps need to be taken to halt the practice of FGM in the Middle East, including implementing changes to legislation and launching widespread campaigns to raise awareness of health risks and challenge the cultural and religious justifications for the practice.

In some countries, like Egypt, FGM has been totally outlawed, while in others, like the UAE, the process has been outlawed in hospitals and official institutions. However, evidence suggests that the practice still occurs in these countries despite these legislative changes, due to social pressure and local customs.

Awareness raising campaigns must therefore accompany legislation, in order to facilitate the collection of reliable data, increase understanding of the potential health risks and begin to change public opinion.

Such campaigns must focus on reducing the stigma surrounding the issue in order to encourage women and girls who have undergone the practice to speak out about their experiences. By reducing the stigma, more moderate religious authorities will also be more inclined to add their voices to the debate and argue against the practice.

One way of doing this might be for high profile figures in the region to speak out against the practice in order to tackle the taboo and spark debate among citizens. This could include celebrities or members of the Royal Families, particularly in the Gulf where their opinions and highly respected.

Legislative changes are necessary, but they cannot be effective without awareness raising initiatives that seek to change public opinion.

FGM in the Middle East – by country

Algeria

FGM is illegal in Algeria under a law passed in 2016 outlawing violence against women, and is punishable by up to 20 years in prison. However, some reports suggest that the practice still occurs in some communities in the south of the country and among Sub-Saharan African migrants in Algeria.

Bahrain

No studies have been conducted into the practice of FGM in Bahrain, however reports indicate that it does exist.

Egypt

FGM is widely considered to be socially acceptable in Egypt, particularly in rural communities, despite the fact that the practice was outlawed in 2007 and is punishable by 5-7 years in prison (and up to 15 if the case results in death or permanent disability).

According to a 2014 health survey conducted by the Ministry of Health and Population, 92% of currently or formerly married girls and women between the ages of 15 and 49 had undergone FGM. The survey showed a decrease in the practice between 2005 and 2014, but estimated that 56% of girls under 19 were expected to undergo it in the future.

A number of high profile cases in Egypt have made the news in recent years, including the historic conviction of a doctor who was sentenced to 2 years imprisonment after initially being acquitted, for performing FGM on a 13 year old girl who died as a result.

Egypt’s Minister of Health and Population set out a plan in 2016 to eradicate FGM (image: Egyptian Streets)

Egypt’s Minister of Health and Population set out a plan in 2016 to eradicate FGM (image: Egyptian Streets)

Iran

FGM is currently legal in Iran, though there is little data available on how often it is frequently it is performed in the country. Some small studies have taken place in the regions bordering Iraq and in the South of the country, which have indicated that 40-85% of women have undergone the practice.

Iraq

Studies conducted in Iraq indicate that 8% of Iraqi women have undergone FGM, with the majority of cases taking place in the Kurdish regions where that figure is over 55%.

These studies show that 88% of women in Iraq believe the practice should end. A law has been passed in the autonomous Kurdish region of Iraq banning FGM, however a corresponding law has not yet been passed by the central Government of Iraq.

FGM has been particularly prevalent in the Kurdish regions of Iran, Iraq, Syria and Turkey (image: HRW)

FGM has been particularly prevalent in the Kurdish regions of Iran, Iraq, Syria and Turkey (image: HRW)

Israel

FGM was reportedly prevalent among some Bedouin tribes in Israel in the 1980s, however the practice has declined during the years since due to various campaigns against it.

Jordan & Kuwait

In Jordan and Kuwait, FGM is reportedly practiced in Muslim communities following the Shafi’i and Maliki schools of Islamic Jurisprudence. Outside of these communities, the practice is uncommon.

Lebanon

FGM is not widely practiced in Lebanon. This could be because of high percentage of Lebanon’s population that lives in urban areas, while FGM has been shown to take place more frequently in more conservative, rural areas.

Another reason might be that FGM is reportedly more prominent today among certain Sunni Muslim communities, and Lebanon has a considerably smaller percentage of Sunni Muslims than many other Middle Eastern countries.

Libya

Reports indicate that FGM is not widely practiced in Libya except by certain nomadic tribes.

However, Libya’s current position as the “gatekeeper of Africa’s migrant crisis” means that the country is currently home to a huge number of migrants and refugees from sub-Saharan African countries, where FGM may be more widely practiced and socially acceptable.

Sub-Saharan African migrants in a detention centre in Libya (image: Yahoo News)

Sub-Saharan African migrants in a detention centre in Libya (image: Yahoo News)

Morocco

FGM is relatively rare in Morocco and Tunisia, as it is not embedded in the local culture as it is in other parts of the region.

In fact, in 2005 Morocco hosted ministers, politicians and religious leaders from nearly 50 Muslim states for a 2-day conference during which resulted in the “Rabat Declaration on Children in the Islamic World”, which emphasised FGM and other harmful practices discriminating against girls, underlining it as against Islam.

Oman

FGM continues to take place in Oman and has not been explicitly criminalised – though it is oficially banned in Omani hospitals. According to a 2014 study, 78% of women interviewed said they had been subject to FGM, with the vast majority conducted at home. 64% of interviewees said that their families still practiced FGM.

According to the Orchid Project, a British charity working to end FGM, there is still a high rate of approval among both sexes for the practice, which continues to occur across the country.

Omani activist Habiba al Hinai has conducted her own survey, which indicates that over 80% of Omani women have been subject to FGM. Her activism on the issue has sparked debate in Oman, and the Ministry of Health has since mentioned it as a matter of concern.

Qatar

Reports indicate that cases of FGM exist in Qatar, but the practice is in decline. There are no studies outlining the number of cases.

Saudi Arabia

Local sources claim that the practice of FGM is rare within Saudi Arabia, though it is acknowledged that FGM is practiced within some communities in the Kingdom, particularly in the southern region bordering Yemen.

The procedure, which is legal in Saudi Arabia, is typically carried out by a Daya (an elderly female birth attendant) when a baby girl is a few days old, though in some cases it takes place at other times during childhood, adolescence, before marriage or during a first pregnancy.

Some believe that the practice may be spreading as a result of the influence of highly conservative religious clerics who argue that the practice is linked with Islam.

Saudi women’s rights activist Manal Al-Sharif gave a moving account of her own experience of FGM, growing up in a conservative neighbourhood in Mecca, in her book, Daring to Drive – read more about Manal here.

Syria and Turkey

There is little evidence to suggest that the practice is prevalent in Syria or Turkey. Though some reports have suggested that FGM is commonly practiced by Kurds, research undertaken by organisations based in the region has drawn a distinction between the various Kurdish communities. This research found that Kurmanci Kurds, who occupy areas of norther Syrian and southern Turkey, do not typically practice FGM, unlike Gorani Kurds in Iraq.

UAE

Research performed by the WHO suggests that FGM is prevalent in the UAE. In a 2011 survey, 34% of Emirati women questioned said that they had been circumcised and related the practice to customs and tradition.

FGM is widely debated in the UAE and, though it is not illegal, the government has prohibited the practice in state hospitals and clinics.

Yemen

FGM is not practiced in many Yemeni governorates, however in some parts of the country up to 84% of women have undergone the procedure. Nationwide, 19% of women and girls have undergone some form of FGM.

In 99% of women, the procedure takes place within the first year of birth (with 93% within the first month). It is usually practiced by older women from local villages, who were taught to perform the procedures by their mothers or grandmothers and continue to pass it down to their own daughters and granddaughters. Anaesthetic is rarely used.

Some prominent Yemeni religious leaders of the Shafi’i school of Islam consider FGM a religious obligation. The Zaidi Shia community, which represents roughly a third of Yemen’s population, generally does not practice FGM.

A 2001 governmental decree prohibited the practice in public and private health facilities, though it is almost always carried out in the home of the baby. In 2014, a Child Rights bill was proposed that criminalised FGM. The current war in Yemen has thrown this process into disarray.

Organisations working to stop FGM in the Middle East:

Stop FGM Middle East

Stop FGM in Kurdistan

28TooMany

Orchid Project

WADI

Equality Now

End FGM European Network

If you found this interesting, you might also like:

Art as a means of recovery for the Yezidi women who escaped ISIL

“Driving while female”: Manal al Sharif and the fight for women’s rights in Saudi Arabia

Cairo’s Ballerinas are redefining Egyptian society

Cover image: Feminism in India