As avid podcast listeners will know, the New York Times recently wrapped up its binge-worthy 10-part podcast series, Caliphate, which delves into the inner workings of the billion dollar operation that is/was the Islamic State.

With thousands of 5-star reviews on iTunes, this dramatic podcast has hooked people by sharing unique, first-hand insights into what life is like inside the Caliphate, the terror they have inflicted on local populations, and what motivates people to travel to Syria and Iraq to join ISIS.

Caliphate’s producers have received a tumult of praise and accolades for the podcast, but also their fair share of criticism from those who question the ethics of their journalism, particularly regarding the treatment of their subjects.

The addictive podcast has also raised a number of key issues including the role that journalism should play in society and in conflict zones, the fragile situation in Iraq, and the difficulties facing Western governments in apprehending and bringing to justice the former ISIS fighters who have returned home.

“Fat-shamed by ISIS”

Caliphate was produced by Andy Mills and follows the work of Rukmini Callimachi, an award-winning Romanian-American journalist and NYT foreign correspondent reporting on Al Qaeda and ISIS.

Callimachi’s coverage of the group has brought her notoriety among their ranks, and she discusses on the podcast how she has received various threats from the group’s members, who have even targeted her weight. The podcast follows Callimachi in her reporting over a period of months as she interviews a young Pakistani-Canadian who goes by the name of Abu Huzaifa.

Huzaifa was radicalised online and left Canada for Syria in 2014 to join ISIS. He speaks to Rukmini about his time there, explaining how he worked in the Caliphate’s law enforcement department as a policeman. Disillusioned by the systematic violence committed by ISIS members – including himself – he returned to Canada filled with remorse.

Huzaifa’s conversations with Callimachi are somewhat confusing to listen to. One minute, he sounds like an ordinary Canadian kid talking about school and his parents. The next, he’s detailing how he killed someone in Syria. It forces the listener to see commonality with young the recruits who are radicalised and consider how ISIS manages to justify the violence its members commit.

Dabiq, ISIS’s Engish-language media publication

Dabiq, ISIS’s Engish-language media publication

After speaking with Callimachi, Huzaifa was apprehended by the Canadian police, but to this day they have been unable to prosecute him due to lack of evidence. When speaking to the Guardian, Callimachi explains that Huzaifa initially seemed remorseful, but later seemed to dig back into the radical ideology that led him to join the group in the first place.

“I think he started to get really cocky. And to go: ‘Oh, they can’t have me. They’ve got nothing on me, I’m totally free.’ I actually think he’s more radicalised now than when we started.”

Mills and Callimachi also travel to Mosul, where they follow the trail ISIS left behind as areas of the city are liberated by Iraqi forces. Here they find documents explaining how the group managed its bureaucracy and finances. They travel across Iraq, interviewing family members of former ISIS fighters and Yezidi women who were held in captivity and systematically raped and abused.

The podcast, which raced straight to the top of the iTunes chart, has shot Callimachi rather unexpectedly into the spotlight. She has since been hopping between talk shows and interviews discussing her work, Abu Huzaifa’s controversial case and the inner workings of the Islamic State. The podcast has been widely praised for its unique insight but it has also received strong criticism from those who question its ethics.

A fair price to pay for a ‘scoop’?

Possibly the most controversial issue raised by Caliphate is the treatment of subjects and victims of violent crime by journalists in the name of getting a good story. The podcast’s harshest critics have even gone as far as to suggest that its producers used the victims they interviewed for fame and accolades.

One of the episodes hears the story one of thousands of Yezidi women who was kidnapped, held captive, raped and sold by ISIS fighters after the group’s brutal siege of towns in northern Iraq in 2014. During the episode, Callimachi and Mills interview a fighter who supposedly bought, enslaved and repeatedly raped a young Yezidi woman. When he denies abusing the woman, Callimachi puts her on the phone to talk to her former captor and confirm his crimes.

What is unclear during the episode is how willing the woman was to speak to her captor and what support, if any, she received from the New York Times after what was inevitably a hugely traumatic experience.

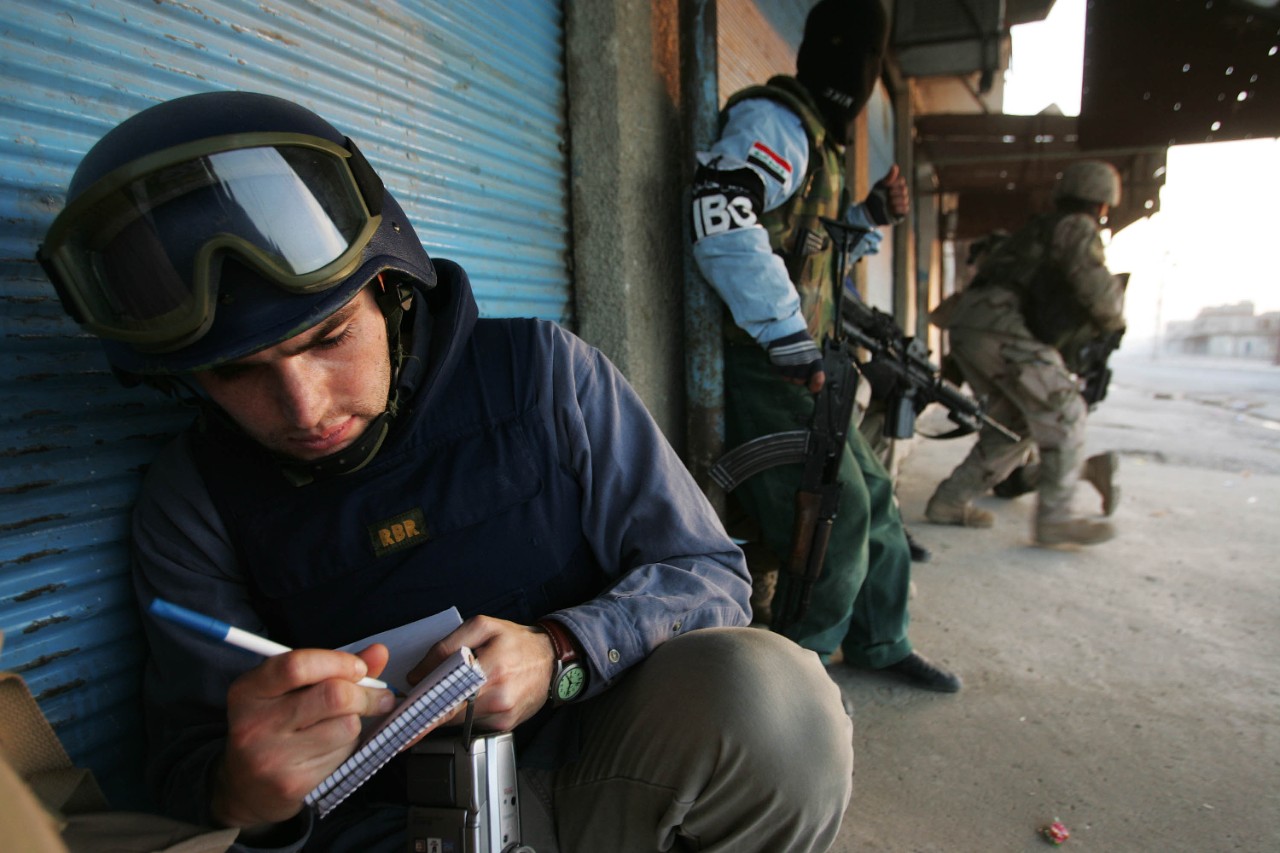

A war correspondent in Iraq (image: The Odyssey)

A war correspondent in Iraq (image: The Odyssey)

This raises the long-debated issue of how journalists operate in conflict zones when dealing with victims of violence and trauma. Critics of the podcast have suggested that the incident reflects a pattern of Western reporting on conflict zones, where the humanity and agency of survivors are sacrificed in the name of getting ‘scoops’.

Since the plight of the Yezidis rose to prominence in the Western media, a number of Yezidi women have spoken out about their treatment by journalists, some saying that their privacy was violated by interviewers while others said they had been coerced into telling their stories and reliving their traumas.

“They take our stories and they don’t do anything for us. They come here and they take videos, take pictures, ask questions, and then they go.”

Ensuring no further harm comes to victims of trauma is a difficult issue not only for journalists seeking to share victims’ stories, but also for healthcare professionals, law enforcement officers and judicial officials. It is one of the many issues the Iraqi Government is currently grappling with as it seeks to identify victims of gender-based violence and bring perpetrators to justice.

A displaced Yezidi girl near the Iraqi-Syrian border (image: Ahmed al-Rubaye)

A displaced Yezidi girl near the Iraqi-Syrian border (image: Ahmed al-Rubaye)

Endangering Iraqi lives?

Another challenge Iraq faces in the wake of the Islamic State’s reign of terror is weaving fractured societies back together and preventing violent acts of revenge, as was also highlighted by critics of Caliphate.

In another episode of the podcast, Callimachi visits the family home of an ISIS bureaucrat and interviews his mother and his wife. She states his full name and also refers to the family’s tribe, where they live, and details of their wealth and social standing.

Critics have slammed this move as careless and dangerous, saying that identifying them like this exposes the family to possible revenge attacks by Iraqis who opposed ISIS. Such attacks against the families of former fighters have increased in Iraq since the Iraqi army recaptured Mosul from the militants, as some Iraqis choose to take justice and revenge into their own hands.

This is a poignant reminder of how fragile Iraqi society is today – ISIS may be gone, but the wounds they inflicted on Iraq are still well and truly open.

The Iraqi government now faces the daunting task of rebuilding the infrastructure and societies destroyed by the group. One of the greatest challenges is transitional justice. It is extremely difficult for the Iraqi authorities to identify former ISIS fighters and even more difficult to find enough evidence to convict them. Prisons are filled with suspects, while worrying stories of torture and summary executions continue to circulate in the media.

The terrorist next door

Though the situation is very different, Western law enforcement and justice systems face similar challenges. Former fighters like Abu Huzaifa continue to trickle back to their home countries, whose governments have little hope of finding the evidence to convict them.

Just this month the BBC reported the story of a Yezidi victim of ISIS who was resettled in Germany, only to come face to face with her former captor on the street near her new home.

Journalism vs law enforcement

Finally, one of the fundamental issues the podcast unintentionally raises is the overlap of investigative journalism with law enforcement and public policy. As the podcast highlights, one aspect of Callimachi’s work over the last year has been entering recently-liberated Iraqi areas and searching through the troves of documents ISIS have left behind for insights into the way the group manages itself.

She has reportedly taken over 15,000 pages of documents out of Iraq, instead of handing them over to the security services. Not only are these documents potentially historically significant, but experts warn that when journalists fail to share such information with the authorities, they risk compromising the workings of the judicial system and preventing due and fair process.

Experts have also warned that Caliphate, along with other crime dramas like the wildly popular Serial, are also blurring the lines between narrative fiction and reality and drawing the wrong kind of attention to violent crimes.

(image: Ozy)

(image: Ozy)

Despite criticisms, Caliphate is a must-listen for anyone interested in ISIS, terrorism or the Middle East. It not only provides a fascinating account of life inside the Islamic State, but it also raises important issues about journalism, ethics, and the challenges of reconciling and rebuilding after conflict – something a number of regional countries will likely be dealing with for a long time.

If you found this interesting, you might also enjoy:

15 essential podcasts to help you understand the Middle East

Fauda: The Israeli Netflix drama that’s got the Middle East talking

Iran’s City of Lies: Extraordinary stories of love, sex and death in Tehran