Mahra, the easternmost province in Yemen, has garnered interest and intrigue over the years for being distinct from the rest of the country. Its history, culture, language, tribal norms and geography set it apart from other Yemeni governorates, and in reality many of its inhabitants share more in common with their southern Omani neighbours than their own countrymen.

Since the outbreak of civil war in Yemen in 2015, Mahra’s geographical remoteness has kept it isolated from the majority of the fighting. But since 2017, Mahra has become a focal point in a proxy competition between intervening regional powers that threatens to destabilise this unique bastion of stability and relative peace in a country at war.

This article provides a historical and cultural introduction to this fascinating and exceptional part of Yemen, which has become intrinsically tied to the unfolding political dynamics both inside Yemen and elsewhere in the region.

Mahra, is the second largest governorate in Yemen by size, bordering Oman to the east and Saudi Arabia to the north. It’s geographical diversity sets it apart from the rest of Yemen, with the Empty Quarter desert taking up much of the south of the province, providing a stark contrast to the coastal climate and lush greenery to the north and the east.

Its population – numbering approximately 350,000 – is made up of predominantly Sunni tribes, although there is also a strong tradition of Sufism in the region. Mahris have a distinct sense of regional identity and independence and have historically been marginalised by the central authorities. Since the 15th century, Mahra was an independent Sultanate that also encompassed Socotra, the Yemeni island famous for its wild and unique natural life. The Sultanate was abolished in 1967, when the People’s Republic of South Yemen was founded, and the governorate later became part of Yemen after the unification of the north and the south in 1990.

The inhabitants of Mahra adhere to a tribal code of conduct shaped by the region’s distinct culture and its proximity to Oman. For Mahris, loyalty to kin is paramount, and there exists a long tradition of mediation and reconciliation where conflict emerges between families and tribes. These traditions have developed largely out of Mahra’s history of self-governance: the ability to solve internal problems and disputes has been key to the region maintaining its sovereignty and unity.

The tribes of Mahra share blood lineage with the tribes of Dhofar, the southern governorate of Oman which borders Yemen. Many cultural commonalities exist between Mahris and Dhofaris thanks to the history of cross-border migration and cooperation. In recent years, Oman has granted citizenship to many Mahris and made it easier for many to move to Oman than other Yemenis and foreign nationals.

The coastline on either side of the Oman-Yemen border is similar in climate, while inland areas of both Mahra and Dhofar are mountainous and have their own, wetter climate that is distinct from the desert conditions of other parts of Oman and Yemen. Like Dhofar, the mountainous region in Mahra experiences the ‘Khareef’ (autumn) season, during which heavy rains turn the area lush, grassy and green. Also like southern Oman, Mahra is known for frankincense agriculture. Throughout history, frankincense has been cultivated in southern Yemen and Oman and transported to be traded around the world.

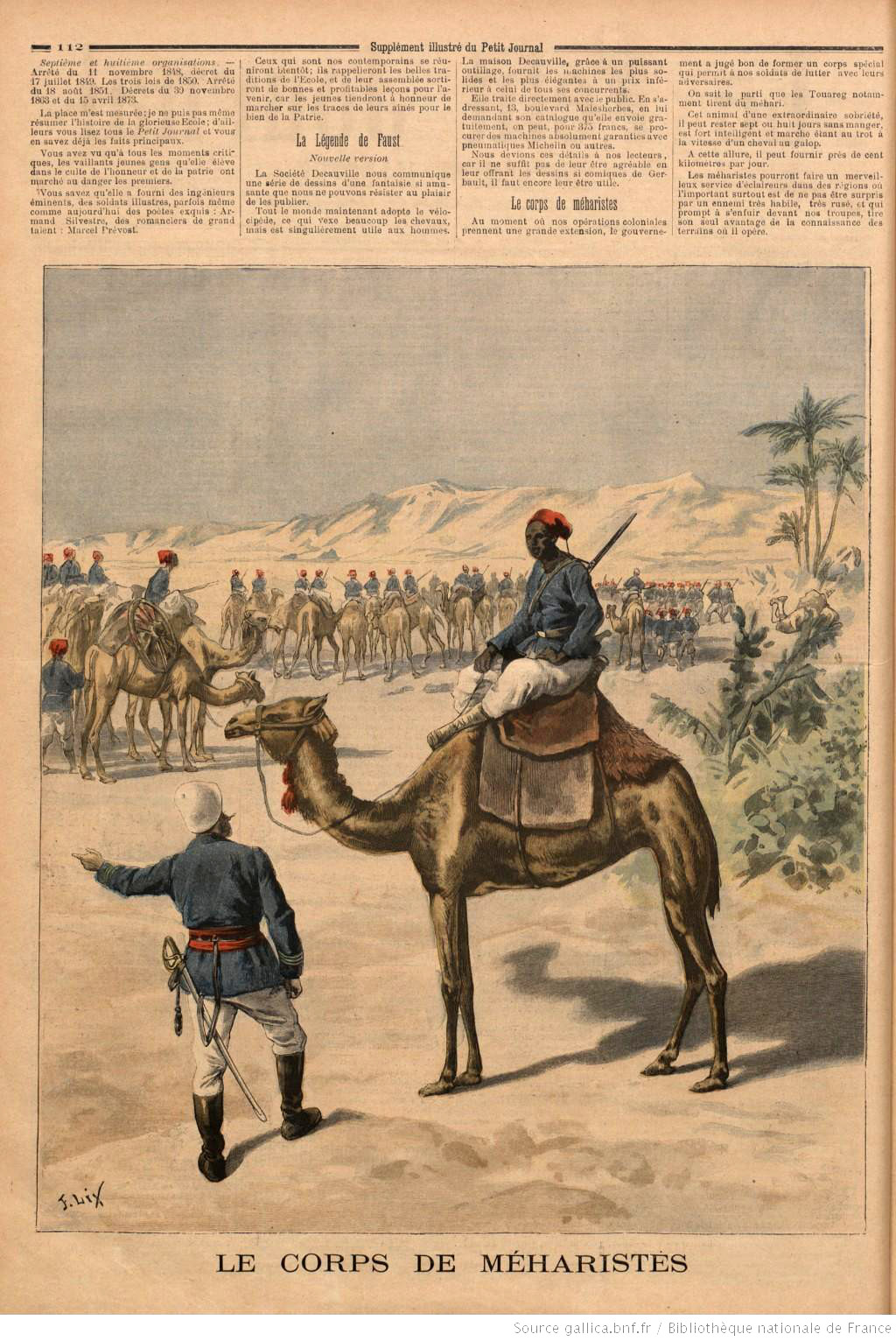

Aside from its unique culture, climate and crossovers with Oman, there’s another thing that Mahra is famous for: camels. The Mahri camel is a distinct breed known for their speed, agility and toughness. Originating in Mahra, the camels were introduced to North Africa during the Islamic conquests – in which Mahri tribes played a key role, largely thanks to the ability of their camels.

During the colonial period, the French took advantage of the Mahri camels’ capability, establishing a Camel Corps called the Méhariste (or the Free French Camel Corps), which was part of their Armée d’Afrique. Today, the Mahri camel is found in most countries in Northern Africa, where they are known as either Mehari camels or Sahel camels.

Since the outbreak of conflict in Yemen in 2015, Mahra has remained nominally under the control of the internationally recognised government of President Abd Rabbu Mansour Hadi. But although the governorate has avoided the brunt of the violence it has seen an influx of Yemenis displaced from their homes elsewhere in the country. Moreover, while Mahra is geographically isolated from the frontlines of the war, it has become a focal point in an ongoing proxy rivalry between regional powers seeking to entrench their authority in the governorate.

Mahra is geo-strategically important to regional regimes due to its location on the Omani border, which makes it a key entry point for weapons and logistical support en route to the warring parties. Frequent accusations have been made about the Yemen-Oman border crossings being used for the illicit transfer of Iranian weapons destined for the Houthis, meaning controlling the borders is in the interest of the Saudis and their allies.

Mahra is also a key strategic location for commercial and military interests in the Indian Ocean and East Africa; Saudi Arabia, for example, has long been rumoured to have the intention of constructing an oil pipeline through Mahra to give it direct access to the Indian Ocean.

From late 2017, Saudi Arabia and the UAE began to upgrade their involvement in Mahra, establishing military bases and funding certain tribal elements in an attempt to expand their influence. This stepped on the toes of their Omani allies, who have long been the dominant international actor with influence on the ground in Mahra through soft power programmes and long-established relationships with local tribal leaders. The Saudi intervention sparked an opposition movement among locals, culminating in demonstrations in 2019 which were believed to have been backed by Oman.

Driven by different agendas, the Saudis and the Omanis have continued to empower different tribal actors and groupings in the governorate, disrupting the local balance of power and threatening to destabilise what has so far remained a relatively peaceful bastion of stability in a country at war. Instead of dividing Mahra, international actors should seek to build on the region’s tradition of reconciliation and conflict-resolution, using this as an example that could be replicated at a local level elsewhere in war-torn Yemen.

For a more detailed overview of what’s happening in Mahra, see the following articles:

Mahra, Yemen: A Shadow Conflict Worth Watching – Ahmed Nagi, Carnegie

Yemen’s Al-Mahra: From isolation to the eye of a geopolitical storm – Yahya al-Sewari, The Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies

Emiratis, Omanis, Saudis: The rising competition for Yemen’s Al-Mahra – Eleonora Ardemagni, LSE Middle East Centre

Oman’s Boiling Yemeni Border – Ahmed Nagi, Instituto Per Gli Studi Di Politica Internazionale

Inside East Yemen: The Gulf’s proxy war no on is talking about – Bel Trew, The Independent

If you found this useful, you might also like:

A reckoning: Coronavirus in war-torn Yemen

African Arabs: Migration and cultural exchange on the Swahili coast