Cultural appropriation can be a bit of a scary term. This is largely because it’s mostly thrown about on Twitter as fuel for #cancelculture, particularly regarding the behaviour of celebrities and big brands. It’s most widely recognised in the fashion industry, but also extends to other areas such as food.

Cultural appropriation can be difficult to define and the line between appropriation and appreciation is often very fine, which can make it tempting to hide from the debate all together for fear of getting it wrong. However, understanding cultural appropriation is incredibly important because it allows us to recognise the power that we have as individuals and consumers to push back against discrimination and exploitation.

What exactly is cultural appropriation?

According to the Cambridge Dictionary, cultural appropriation is “the act of taking or using things from a culture that is not your own, especially without showing that you understand or respect this culture”.

This definition highlights some of the key concepts that are widely agreed to be the hallmarks of cultural appropriation:

- The idea of one culture stealing certain aspects of another culture for its own benefit.

- The lack of recognition and involvement of people of that cultural origin.

This often occurs for the purposes of profit, fashion or novelty – for example for fancy dress.

However, this definition doesn’t fully capture the reasons why cultural appropriation can be harmful and, in the worst cases, downright exploitative.

Racism, colonialism and cultural plagiarism

The exchange of cultures between humans is natural and fluid. It’s been happening for millennia, but it is especially prolific in the globalised world and the internet age, where we’re all connected by technology, particularly in big, multicultural cities like London.

Generally speaking, it’s not difficult to understand why people might find it offensive when people from one culture use objects or rituals that are sacred or have religious meaning in another for fun or profit.

But the line can be slightly more blurred when it comes to everyday objects, other cultural symbols and traditional dress. In many cases it’s not just the act of cultural appropriation itself that causes the most harm, but the context within which it occurs.

It’s absolutely crucial to take into account the historical, political, economic and social context, because cultural appropriation – or cultural plagiarism as it’s also known – is intrinsically tied to histories of racism and colonialism.

Many of the cultures that are commonly being appropriated today – for example, black, Arab, Asian or indigenous cultures – have been historically oppressed and/or violently colonised by white people and racist political systems.

When there’s a history of one racial group taking something from another (such as labour or natural resources extracted under oppressive, racist or colonial systems), it is understandably seen as offensive and even exploitative to then take aspects of that culture as well, for personal or commercial gain.

For example, in the United States black people have faced discrimination – and in some cases active punishment – for wearing cornrows in their hair. So when white celebrities wear the same hairstyle for fashion or for fun, it can be extremely upsetting and disempowering. The use of black culture by white celebrities must be seen within the context of a country that is still coming to terms with its deeply racist history and systems.

Similarly, North African cultures have been a huge source of inspiration for the European fashion industry. However many of the huge international brands that have capitalised on aspects of North African culture have done so without giving credit or recognition to the cultures and artisanal communities that inspired and created their products.

This cannot be seen outside of the historical context of European domination of North Africa during the 19th and 20th centuries, when violent and oppressive colonial systems allowed for the exploitation of North African countries such as Morocco and Algeria.

The remnants of those colonial systems have remained in place in many cases, allowing European and international companies to continue to profit from this history, by using cheap North African labour and resources in the manufacturing of their products, without allowing those communities to share in the profits.

This represents a global trend, whereby the so-called Global North (i.e. higher income or ‘Western’ countries) profits from the cheap labour and resources of the Global South (lower income or ‘developing’ countries). So to do this while also profiting from cultural plagiarism is not only offensive, but also perpetuates these economic systems on a cultural level.

Examples of Cultural Appropriation

There are a number of high profile examples of cultural plagiarism – in many cases involving the same individuals and brands who continue to practice it even after being called out and criticised.

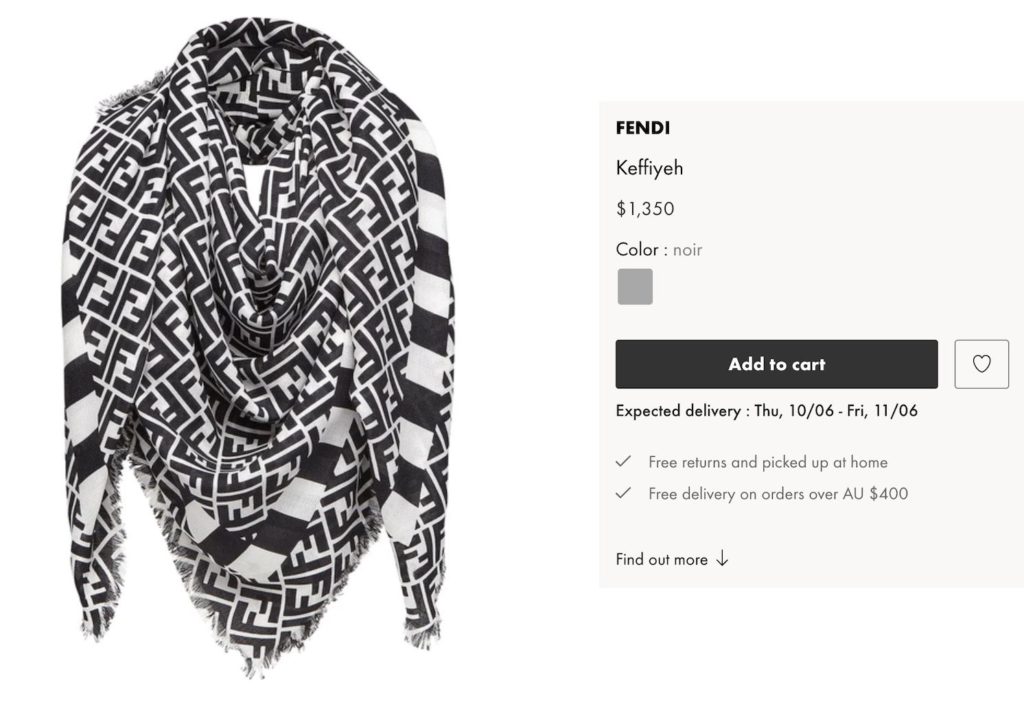

A recent, high profile example involved fashion houses Louis Vuitton and Fendi who, in May 2021, were slammed for offering their own branded, designer versions of the traditional Palestinian keffiyeh – the black and white scarf that has become symbolic of Palestinian culture and resistance against Israeli occupation.

The brands were selling the scarves – which are widely available online from Palestinian businesses for less than $30 USD – for hundreds, if not thousands of dollars, with no acknowledgement of their Palestinian origin, sparking a backlash on social media.

This occurred during a period of heightened online awareness of the Palestinian struggle as a result of the May 2021 #SaveSheikhJarrah campaign, leading many to criticise the brands for attempting to profit from Israeli war crimes and human rights abuses in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip.

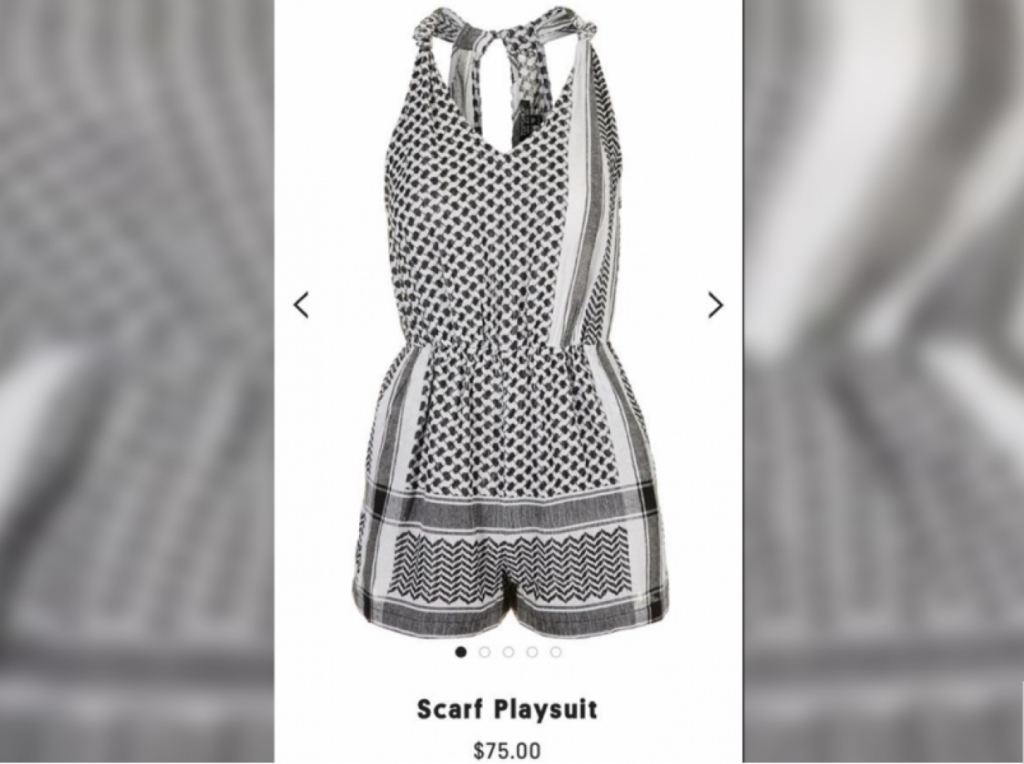

High street brands have, in the past, been equally guilty of appropriating the Palestinian keffiyeh without reference or credit to sell clothes. For example, Topshop came under fire in 2017 for a keffiyeh style playsuit, which critics called “offensive and demeaning“.

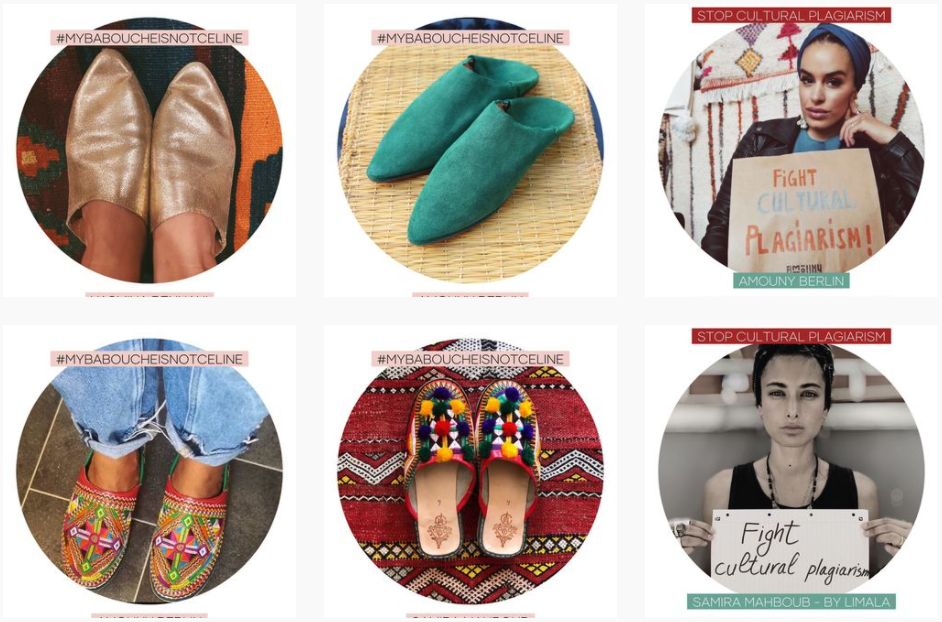

Similarly, luxury French brand Céline has been accused of cultural plagiarism for selling Babouche – traditional Moroccan leather slippers – for over €900. Critics have argued that the Moroccan artisans who created the Babouche were not compensated anywhere near that amount, and that the brand failed to acknowledge or give credit to the cultures and artisanal communities from which the Babouche originate.

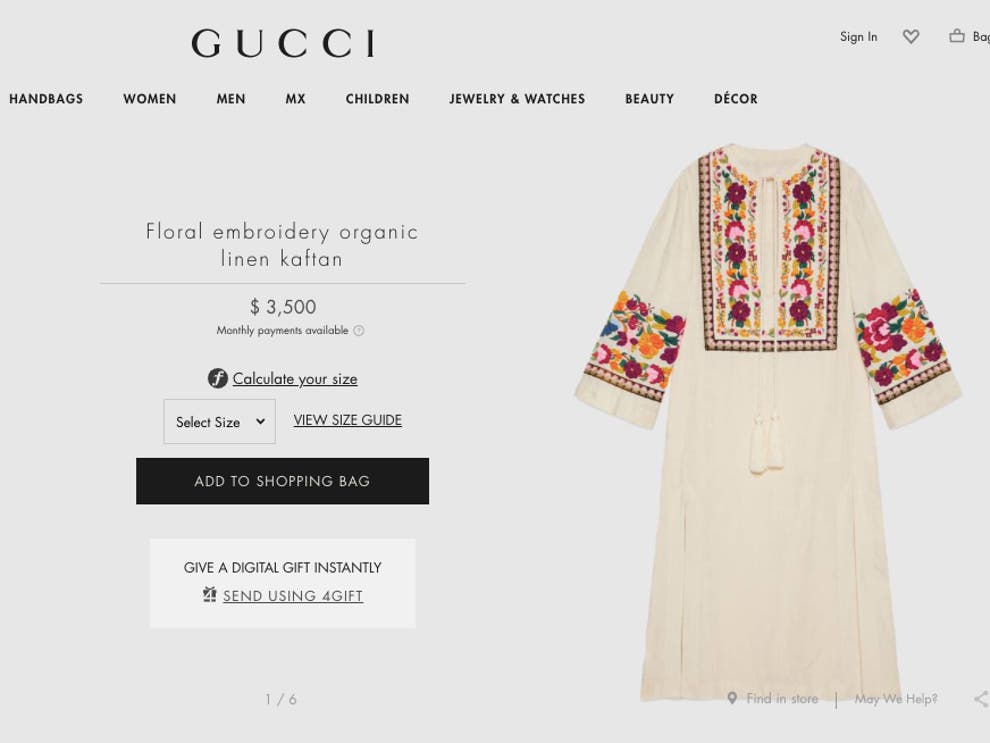

Gucci has also had its fair share of criticism for cultural appropriation, most famously for its 2018 Milan Fashion Week show featuring white models wearing Sikh turbans, headscarves, and headpieces resembling Asian architecture. In June 2021, the fashion house was also called out for selling a $3,500 ‘kaftan’ resembling the kurta commonly worn across South Asia. Similar items are widely available in local markets for less than $10.

Cultural appropriation vs cultural appreciation

A common argument heard from those who have been criticised for cultural appropriation is that they are merely appreciating, rather than plagiarising or appropriating another culture. It is important to understand the difference between the two, in order to avoid offending others or perpetuating harmful stereotypes and economic systems.

This video by VICE is a really helpful explainer of the difference between cultural appropriation and cultural appreciation:

According to those interviewed in the video, appropriation occurs when you pick and choose things from other cultures as merely an accessory, costume or trend or to make money, without proper reference. It’s appropriation, they say, when the action does not come from an authentic or genuine place.

Cultural appreciation, on the other hand, is when you work with people from the culture you’re taking inspiration from, when you give credit and contribute something back to that community.

Dos and Don’ts

Much of the cultural appropriation debate focuses around businesses and brands. From a business’s point of view, avoiding cultural appropriation involves three key things: transparency, credit, and inclusion.

Businesses should:

- Consult with people of the cultural origin they’re taking inspiration from to ensure they are using it in a conscious, respectful and responsible way.

- Hire manufacturers and models from that particular culture to make and model the product.

- Be open and transparent about the source of inspiration and give credit to the artisans who made it.

- Acknowledge mistakes and stay open to learning from them.

Yet we also have a responsibility as individuals to avoid appropriation and empower those communities who have historically been exploited and marginalised. Here are a few things you could do:

DO

- Use your platform to share the voices of people from cultures that have inspired you and to express your appreciation for their artisanal skills.

- If you’re using or wearing something from another culture, make sure you – and other people too – know where it came from and how it came about.

- Buy from businesses owned by people of other cultures, or businesses that give back to marginalised communities and victims of exploitation.

- Increase the level of diversity in your own life – and particularly your social media feed! Follow more black, brown and indigenous people and businesses, share their work and buy from them!

DON’T

- Wear something for fashion or fancy dress without at least a basic understanding of its cultural significance.

- Don’t share something without proper reference if it borrows from another culture.

- Don’t buy from brands that you know are guilty of – and unapologetic about – cultural appropriation or plagiarism.

So if you want to wear babouche because you love Morocco or you’re interested in Moroccan culture, that’s fine – in fact, it’s great! But just make sure you buy them from a Moroccan business, or a business that supports Moroccans and celebrates Moroccan artisanship. Even better, share your new babouche on social media and give that business or artisan a shout-out, acknowledging the Moroccan origin!

People and businesses to follow

There are a number of wonderful people, platforms and businesses working hard to end cultural plagiarism. Here are three of our favourites – these incredible, inspiring women have built beautiful, responsible businesses rooted in the celebration of local cultures and the decolonisation of their industries:

Samira Mahboub (@samiramahboub)

Samira Mahboub is a Moroccan-German model, performance artist, Postcolonial and Intersectional Feminist Scholar, activist and social entrepreneur. She is the co-founder of Limala, a cultural project and social enterprise selling handmade Moroccan rugs and traditional products made by Moroccan women in the Atlas Mountains.

Limala uses storytelling and visual narrations to celebrate the art of traditional Moroccan crafts and the artisans who make them. Through her work, she not only highlights the beauty and uniqueness of Moroccan cultural heritage, but also seeks to reclaim it for Moroccans and end the cultural plagiarism that has taken root in the fashion and luxury goods industries over the years as a result of post-colonialism.

Samira is an ambassador of L’Balgha (@l’balgha), an online platform that started the #mybaboucheisnotCeline hashtag campaign, which seeks to reclaim Moroccan heritage for Moroccans and fight cultural plagiarism.

Jeanne de Kroon (@jeannedekroon)

Jeanne de Kroon is a former model, sustainability activist and founder of Zazi Vintage, an Amsterdam-based ethical fashion brand that aims to connect consumers with the local communities – and especially women – around the world who make their clothes.

While working as a model in New York, Jeanne was disillusioned by the lack of connection the fashion industry seemed to have with the origin of the garments they were selling. All of Zazi’s designs highlight the stories, cultural significance, and artisanal traditions of their communities of origin in Afghanistan, India, Nepal, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan.

Sana Javeri Kadri (@sanajaverikadri)

Sana Javeri Kadri is a former food photographer turned activist, entrepreneur and founder of Diaspora Co., an ethical spice company on a mission to decolonise the spice trade and apply farm to table ethics to the supermarket spice aisle.

Diaspora Co. is rooted in the concepts of equity and social justice. It is not only a fair trade company working directly with local farmers and communities, but it is also a digital platform and community educating people on the colonial history of India and the cultural significance of spices.

Want to learn more?

Here are a few resources on cultural appropriation and appreciation that you might find helpful. If we missed anything, leave a comment and let us know! We’re always on the lookout for new resources to share with our community.

- Cultural Appropriation: Whose problem is it? – BBC, September 2018

- The Ethics of Cultural Appropriation – Conrad G. Brunk and James O. Young, 2012

- Going Native: Indians in the American Cultural Imagination – Shari M. Huhmdorf, 2001

- White Negroes: When Cornrows were in Vogue … and Other Thoughts on Cultural Appropriation – Lauren Mich Jackson

- The Difference Between Cultural Appropriation And Appreciation Is Tricky. Here’s A Primer. – Huffington Post, February 2018

- Your Terra Incognita is My Home – Weekday Blues, July 2010

- 100 Black Owned Businesses to Support – Forbes, June 2020

- 8 Indigenous-Owned Beauty and Lifestyle Brands to Follow on Instagram – Sunday Riley, August 2020

- 10 Arab Women-Owned Businesses to Support – Hiba Traboulsi, Yalla Let’s Talk

- 6 Social Enterprises Supporting Local Communities in the Middle East & North Africa – Pink Jinn, June 2020

❤️