Scent is one of the most powerful aspects of personal adornment. It lingers in the air long after a person has left, it brings back memories of places we’ve been or people we’ve loved, and it has a proven influence on our state of mind: from soothing lavender to pick-me-up rosemary, the powers of fragrance have been known and used for millennia. The use of fragrance goes well beyond that of beautification.

Image: Sigrid van Roode

The invisible world

One of the oldest uses of fragrance is to connect us to the spiritual realm. Since the days of Ancient Egypt and the empires of Mesopotamia, frankincense was burned to honour and please the gods. The act of burning is a transformation in itself: the small grains of resin vanish, and in its place a warm, fragrant smoke appears that easily fills an entire room. It is not difficult to see how this might be interpreted as the presence of a divine being.

Indeed we find references to fragrance in ancient literature where the presence of a delightful scent indicates the otherwise imperceptible presence of a god or goddess. Similarly, the presence of a disagreeable smell heralded the arrival of evil beings. In later times, being clean and well-groomed became a prerequisite for Muslims. Musk, the favourite scent of the Prophet Mohammed (PBUH), is still highly valued, as is ‘ūd.

Guests, time and space

Fragrance is also an important agent in social interactions. In many countries, great care is taken before guests arrive to fragrance those parts of the house where they will be received and entertained. As such, fragrance functions as a marker of space. Upon arrival, the guests are welcomed with incense and perfume. Born of the need to refresh oneself after a journey, this custom is a beautiful way of expressing hospitality: a visitor is transformed from a stranger into an honorary member of the household through the act of enveloping him or her in the scent of the house.

Many incense mixtures, or bukhūr, were created by the women of the household themselves following family recipes, and a woman would be praised for her skill in blending fragrances as much as she would for her embroidery or cooking talents. When entertaining guests, fragrance also functions as a marker of time. When the visit has ended, the hostess will envelop her guests in fragrance once more. Perfumed oils are passed around and applied by each guest, after which a brazier with incense is passed around as well. Well perfumed, the guests will take their leave, and will carry a sensory memory of their visit for a considerable time after they have left. Nowadays, this tradition is also performed using high end perfumes: the form may have changed, but the expression of hospitality remains as solid as ever.

Image: Sigrid van Roode

The journey of life

Fragrance is an incredibly powerful agent of transformation. The use of perfume in and of itself marks the difference between a married woman and an unmarried girl, as it is closely related to the intimacy of married life: fragrance is an important part of sensuality between husband and wife. But there is much more to fragrance, in particular as it relates to weddings.

The lavish use of scent during wedding festivities is not just a form of beautification, but actively guides the bride through her transition into married life. A bride is seen as a particularly vulnerable being, as she is on the threshold between two stages of life: she is not yet a wife, but no longer an unmarried girl. The application of fragrance as part of the bridal preparations serves not only to help her transition into the next phase of her life, but also to protect her: following the lines of analogous magic, evil beings that may wish to harm her are deterred by pleasant scents. Fragrance isn’t only important in weddings, it also plays a role in other transformative periods of life, such as when giving birth and even upon death.

Image: Sigrid van Roode

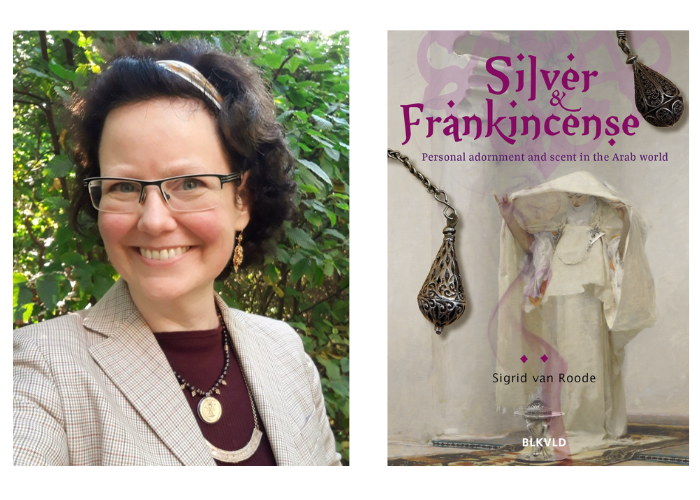

Fragrant jewellery

All of these capacities – the spiritual, the social, and the transformational – are present in fragrant jewellery as well. Jewellery can be created specifically to hold fragrant substances, or can actually be made out of olfactory materials. An example of jewellery designed to hold fragrance are the small containers for ambergris and musk that are worn throughout North Africa and Southwest Asia. Named for the substances held in them, they are called ‘anbra or meskiyya – revealing whether they held ambergris or musk. These containers are little masterpieces in silver or gold, which shows the esteem in which these scents were held.

Types of jewellery created from fragrant materials themselves include the clove necklaces worn in Palestine on the occasion of a wedding. The cloves are soaked in water to make them softer and easier to puncture and thread. This water is then used to bathe the bride on her wedding day, while the necklaces are worn by her female relatives and friends. In some regions, these are paid for by the father of the bride to express his appreciation for these relationships. The scent of cloves beautifully connects all of these sentiments: the bride is protected by this metaphor of friendship and kinship, which is carried into the next stage of her life.

Image: Sigrid van Roode

A meaningful ensemble

The transformative and protective nature of fragrance is not only put to use in jewellery, but features in all aspects of personal appearance. Fragrant components were also sewn into clothing, or added to the henna paste which was used to create patterns on the skin. Fragrance functions as one component of a carefully curated ensemble alongside colour, material and pattern, each carrying meaning and chosen with care. All elements of personal appearance such as dress, embroidery, make-up and beauty, hairstyle and jewellery make conscious use of these. A colour is never chosen randomly, and neither is fragrance.

In personal adornment however, smell is also the capacity that is the first to be lost. Jewellery and pieces of clothing do not keep their fragrance forever, and so our memory of the importance of scent slowly fades as well. Especially when items of dress and adornment have travelled far from home, this olfactory capacity is easily overlooked. The coating of fragrant paste on the inside of bracelets for example, or remaining patches of scented hair paste on pins or ornaments, are mistaken for dirt and cleaned off to make the piece more aesthetically pleasing. But in doing so, we remove the tangible remnants of an invisible power of the piece: the fragrance that would have surrounded the wearer, protected her, and connected her to generations of family history.

Sigrid van Roode is a jewellery historian and archaeologist specialising in personal adornment from North Africa and Southwest Asia. Her research addresses jewellery as part of the material culture of society and focuses in particular on the relation between jewellery and ritual, magic and religion. She is currently working on her PhD, researching jewellery and ritual at Leiden University. With her consultancy company Bedouin Silver she works with museums and private collectors to ensure collected jewellery continues to hold its potential as both historical source and as a carrier of identity. Her books, Desert Silver and Silver & Frankincense showcase her passion for her topic, as does her online course Looking Beyond Jewellery. This fascinating e-course is a window into the traditional jewellery of the Middle East and North Africa, and is perfect whether you’re an absolute newcomer to the world of adornment or a seasoned collector! Discover more about the course or sign up here. You can connect with Sigrid on Instagram (@bedouinsilver) to learn more or to share your stories!

If you’d like to read more from Sigrid, don’t miss her article about jewellery as a form of female financial independence:

Silver Savings: Of Bracelets, Banks And Ladies Who Mean Business

Discover more about frankincense here!