In the summer of 2014, the future of Iraq was hanging by a thread. The so-called Islamic State, or Daesh in Arabic, had rampaged across the north of the country, seizing control of Iraqi towns and cities and imposing their brutal interpretation of Sharia law on the populations who lived there. The Iraqi army units disintegrated in the face of the threat as corrupt commanders deserted their soldiers and left local communities to fend for themselves.

As their influence grew, Daesh gained notoriety worldwide for their horrific use of violence against their enemies and those they deemed nonbelievers. Their victims were caged and set on fire, thrown from buildings, publicly beheaded and shot at point-blank range. The videos and images circulated online, horrifying the world and dragging the international community’s attention back to the Middle East once again.

Media commentators and political pundits began to predict what this would mean in the long term for Iraq, which had already endured decades of sanctions, occupation, violent conflict, terrorism and sectarianism. Many said Iraq could never hold itself together in the face of the threat, predicting that the country would split into three parts along sectarian lines, creating ripple effects that would be felt across the entire Middle East.

It was against this backdrop that Haider Al-Abadi – an Iraqi politician, engineer, and former political exile under Saddam Hussein – became Prime Minister, taking on the role of Commander-in-Chief of a country at war. Over the course of his four-year term, the Iraqi army, alongside thousands of volunteers who joined them in the fight, turned the tide against Daesh, liberating the territory and communities under their control and reclaiming a sense of hope for the future of their country.

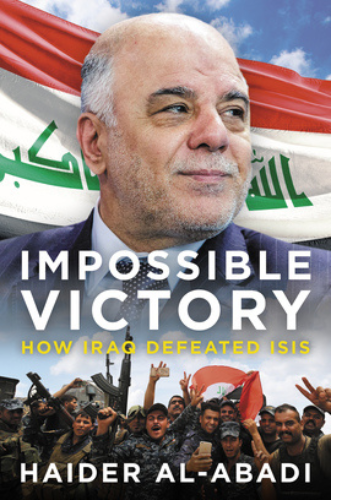

In his new book, Impossible Victory: How Iraq Defeated Daesh, Al-Abadi tells the story of how they did it. The book is a deeply personal account of the recent history of Iraq through Al-Abadi’s eyes, from the early days of Saddam Hussein’s regime through to the US occupation and the war against terrorism and sectarianism that defined his career.

As well as offering an inside account of a defining moment in Iraq’s recent history, the book sheds light on some of the key dynamics shaping the geopolitics of the wider Middle East today.

Many Iraqis think back to the 1950s as a golden age of peace and prosperity for their country. Security wasn’t an issue during this time. The streets felt perfectly safe – even for politicians, who would walk and drive through the city unguarded, greeting ordinary people as they went about their daily lives. Growing up in Baghdad during this period, Al Abadi’s childhood was happy and peaceful, spent playing football with other children on the streets of Baghdad’s affluent Karrada district.

During the late 1960s and early 1970s, the Ba’ath Party seized power and began to tighten their grip on the country, bringing politics into Al-Abadi’s life in his teenage years. By 1979, Saddam Hussein had asserted full control, declaring himself Prime Minister and beginning what would become a decades-long, brutal crackdown on anyone who dared to oppose him.

Pictures of his moustached face began to appear everywhere, and Iraqis stopped speaking about politics in public, always afraid that someone might be listening. Regime critics disappeared in the dark of the night, showing up dead or not at all. Saddam’s family, tribe and inner circle meanwhile began to accumulate wealth and power at lightning speed at the expense of the rest of the country. Within a decade, he had transformed the very nature of politics: Iraq had become a mafia state with Saddam as its godfather.

As a teenager, Al-Abadi joined the political opposition party, Hizb Al-Dawa, taking his first steps into political activism. When he completed his high school education, he travelled to the UK to undertake his PhD in engineering. Little did he know when he stepped onto the plane at Baghdad International Airport in 1976 that it would be the last time he would set foot on Iraqi soil for twenty-seven years.

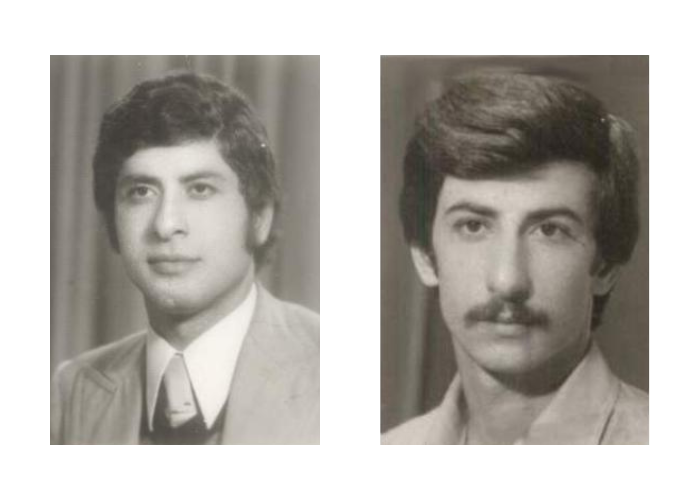

While Al-Abadi was studying in the UK, three of his brothers were arrested and tortured by the Ba’ath regime for their political activism. Two of them were killed and the third was only released ten years later. Al-Abadi soon found that his own passport had been cancelled by the government. He was stranded.

Motivated by the fate of his brothers and undeterred by the culture of fear created by the Ba’ath regime (even Iraqis in exile were targeted with assassinations and forced disappearances), Al-Abadi continued his work with the Dawa Party from London. He rose through the ranks, eventually taking on the role of leader of the party in the UK – all while building a career as an engineer specialising in rapid transit systems. He married an Iraqi woman and had three children, who were brought up to know and love their ancestral homeland despite having never visited it.

Back in Iraq, conflict with Iran and sanctions from the international community had brought the country to its knees, and the drums of war were beginning to sound as hostility grew between the Ba’ath regime and the USA. After 9/11, it looked increasingly likely that the US would invade Iraq. From his home in London, Al-Abadi watched and waited, fearing the destruction and suffering that would inevitably come with war, yet anxious to see the end of Saddam’s iron-fisted rule.

When the US invaded Iraq in 2003, he finally had the chance to return. There were no commercial flights to Iraq at the time, so he flew to Jordan with a friend and made the journey across the border and on to Baghdad by car. After twenty-seven years, he was home.

Over the years that followed, Al-Abadi – like many other political exiles – entered a career in politics, leaving his engineering career behind him. His first position was Minister of Communications. He later chaired the parliamentary economic and finance committees, as well as working as an advisor for multiple administrations.

In Impossible Victory, Al-Abadi shares fascinating insights into the politics of Iraq during these years, explaining how the failures of the US occupation and years of sectarian violence laid the groundwork for Daesh’s rise to power. He also shares how he ended up becoming Prime Minister of a country struggling to control this new terrorist threat – a suitably dramatic tale of intrigue and personality politics that has become familiar in Iraq.

Iraqi politics at that time was defined by corruption, sectarianism and division, and Al-Abadi was seen by many as the least contentious candidate to throw his hat into the ring. His emergence as Iraq’s new leader was therefore a surprise to many, including Al-Abadi himself. The toughest job of his life now lay ahead of him.

Upon taking office, Al-Abadi quickly realised just how dire the situation in Iraq had become. The army was badly under-resourced and insufficiently trained, and lacked the most basic supplies. This, alongside the rampant corruption that pervaded the armed forces, made it unsurprising that they had been unable to withstand Daesh’s onslaught.

Al-Abadi quickly set about reforming the armed forces, rooting out corruption among the highest levels of command and desperately trying to source equipment. He also set out on a world tour, beginning with the United Nations General Assembly, during which he attempted to convince world leaders of the severity of the threat posed by Daesh, making the case for logistical and air support for the Iraqi troops doing battle with the terrorists on the ground.

According to Al-Abadi’s book, that support trickled in at a frustratingly slow pace, forcing him to have difficult conversations with foreign leaders including US President Barack Obama. Meanwhile, back in Iraq, he faced another challenge: aligning the myriad forces who were fighting Daesh together on the ground.

During a sermon in June 2014, Iraq’s most senior Shi’a religious cleric, Grand Ayatollah Sayyid Ali Al-Sistani had called on Iraqis to take up arms and join the fight against Daesh. This led to a surge of volunteers – ordinary citizens inspired by the call to arms – who signed up to do battle alongside the armed forces. The units formed as a result became known as the Popular Mobilisation Units (PMF).

‘I was only a small piece of the puzzle. Everybody had a role to play – politicians, the security forces, the religious establishment, civil society, local communities. I had to trust people to do their jobs, to make their own decisions, to lead their own teams and communities’

The units were difficult to control as they fell outside of the Iraqi security apparatus – some were even directly controlled by foreign forces, such as the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps. But what the PMF lacked in training and organisation, they more than made up for in conviction and religious zeal. They disliked the army, seeing them as cowards and defectors after their initial defeat at the hands of Daesh. The army, meanwhile, looked down on the PMF’s lack of training and structure.

Gradually a balance was struck between the two, harnessing the strengths of both and slowly building trust between them. The first breakthrough came in the town of Jurf Al-Sakhar – a battle that Al-Abadi sees as a turning point of the war. While the world is familiar with the Mosul and other major battles due to the heavy international media coverage, it is these lesser-told stories, peppered throughout the book, that tell the real story of the war.

Iraq has overcome colonialism, dictatorship, occupation, insurgency, sectarianism and terrorism. In defeating Daesh, the most brutal and ambitious terrorist organisation in recent history, we achieved what the whole world thought was impossible.

Stories such as these also offer a compelling insight into the complex dynamics underpinning the major issues that have come to dominate Iraqi politics after the end of the conflict – for example, the rampant corruption that still plagues Iraq, as well as the government’s struggle to control the activities of the PMF during the years since the war.

While many saw the war against Daesh as a purely military fight, Al-Abadi argues in his book that he saw things differently. For him, it was a battle for hearts and minds. A fight for the soul of the country. Every day, according to the book, he was confronted with people who tried to convince him to give up on the people living under Daesh. Even senior military commanders and political figures believed that entire populations were terrorist sympathisers and should not be spared.

But Al-Abadi explains in Impossible Victory that he believed the key to winning the war was winning over the people; convincing communities in the Daesh-held areas that the government was fighting to liberate them – not just their land. The victory over ISIS was, in his mind, the victory of the Iraqi people.

Iraq remains in a state of political deadlock today, after the elections of October 2021 failed to deliver a new government. Corruption seems worse than ever, and militias controlled by warlords exert disproportionate influence over Iraqi politics and daily life. Al-Abadi’s account of the war, as well as his unique perspective on Iraqi politics, come at an important time for outside observers struggling to understand the dynamics driving events on the ground.

Impossible Victory: How Iraq Defeated ISIS was published in April 2022 by Biteback Publishing.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy:

READING LIST | 19 Books To Help You Understand Iraq

The Best Middle East and North Africa Podcasts in 2022 – Politics & History

Freedom Is an Inside Job: Iraqi Activist Zainab Salbi On How To Heal The World