By Joseph Hearn

At sunset, strange concrete forms flatten and spread about the floor, as if spilled water. Interspersed are the more familiar lines of the oak’s leaf and barked trunk. Shaded by a khaki palette of evergreens and conifers, the sculpture garden of Jordan’s National Gallery of Fine Arts provides Jebel al-Weibdeh’s families with a place for rest, conversation, and play. It is a community space – a pivot and thread – bordered by two flat-roofed, sandstone buildings containing the Gallery itself.

As I sit in his office under a beautiful mid-20th-century watercolour, the Gallery’s Director, Dr Khalid Khreis, celebrates these two acres’ pride of place: “It has become one of the most important gardens in Amman, and perhaps even in Jordan.” This is in no small part due to the area’s environmental sustainability, for which it won an international prize at the 2016 Green World Awards.

But Dr Khreis, himself an established artist, stresses that it wasn’t always like this. “When I started as Director in 2002, there was only this one building, and the park was in a bad situation.” In 2004, the combined efforts of the Gallery and Amman’s Center for the Study of the Built Environment transformed the space. The greenery and quiet now marks a welcome departure from Amman’s famous car culture. Wide thoroughfares dominate much of this hilly city, and the Jordan Times recently reported a boom in vehicle ownership in Amman, which has become “an absolute necessity” given the limited public transport.

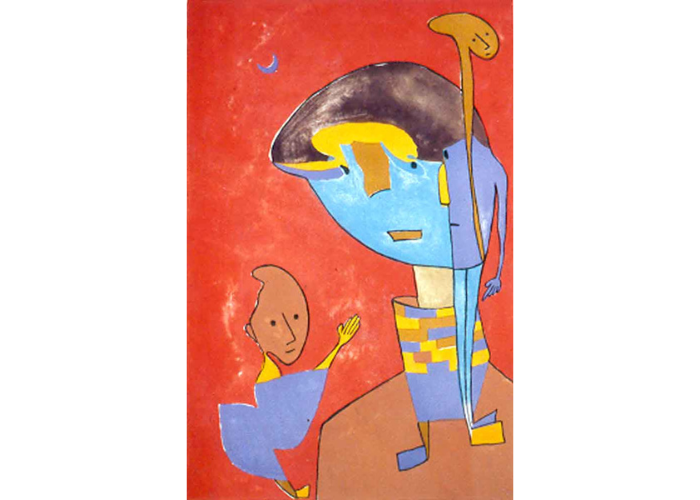

Bordering the garden, over 3,000 artworks from across the Middle East and wider world are displayed and stored in the Gallery’s two buildings. These are rotated, with around a third on display at any one time. “We don’t have enough space to display the entire collection,” says Dr Khreis. “But we try to show everything by varying the displays.” Current highlights include an eclectic collection by the multidisciplinary Lebanese artist Hussein Madi. Earthen-coloured tondos, or circular paintings, sit alongside several acrylics of origami-type birds in bright, popping colours. It’s a thrilling, vibrant combination.

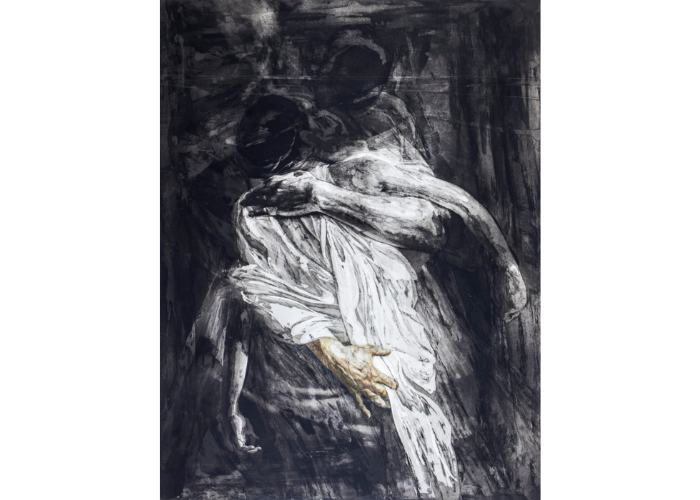

Whilst certain themes are given greater focus, such as calligraphy, the mission of the collection is defined by geography. “We focus on Jordan first, then the Arab world, and then the developing world,” explains Dr Khreis. In the halls, a haunting aquatint by Safet Zec, an artist from Bosnia and Herzegovina, complements a silkscreen from Indonesia and a Jordanian etching.

The art matters much more than the origin, but the gallery aims to promote artists who are perhaps less likely to be embraced by major Western institutions. This is also a reaction to the ferocious commodification of contemporary art. As Her Highness Princess Wijdan Al Hashemi, the Gallery’s founder, recently explained to ArabWorldArt, “We don’t go after big names. Instead of buying one work by a British artist, I buy ten works by ten artists from the Islamic or Arab world. And this is what makes us different compared to other collections. Anyone who has enough money can buy one work from a Western artist. I would pay the same amount to get 20 works by contemporary Arab artists.”

Dreaming of an art hub in Jordan, the Princess established the Royal Society of Fine Arts (RSFA) in 1979, and the Gallery in 1980. An accomplished painter and art historian, since the 1970s she has provided a constant and dynamic impetus for Jordanian art, often in the face of disinterest.

After enthusing about the Princess’ unique passion, Dr Khreis continues, “But otherwise there is very little support for the arts; here in Jordan it is just not enough.” Thus, he is keen to tell the story of Jordan’s recent artistic heritage and current mood:

“In Jordan, as in all Arab countries, we start by looking at the beginning of the 20th-century, when galleries were opened and the visual arts began to grow, first in Egypt, then Lebanon, Iraq, and Jordan. But Arab art has also been influenced by Western art. Sometimes, the artist looks to find and express their identity. They draw on influences including ancient regional civilisations, Islamic art, pop art, and calligraphy.”

“I believe that the artist must be honest with themself first and be creative in whatever way they like. This is very important. If we talk about art in Jordan now, since 1980 there has been some progress. This is even more apparent now, with the up-and-coming generation, who have new formats with which to express themselves, particularly social media.”

And at the National Gallery, change is a constant. In one corner of the famed garden lies a shuttered restaurant, but Dr Khreis has some exciting news:

“From November, this area will be an open space, an arts space, for ceramics workshops, sculpture, printmaking, drawing, and painting. It will be full of life and activities, in the day and late into the night.”

Exhibitions of Arab and Islamic art have been organised by the RSFA in European cities such as Madrid and Cordoba, the latter a celebrated home of Western Islamic architecture. But now more than ever, the focus is on promoting art within Jordan. The new arts space is part of a broader outreach programme, designed to inspire the next generation. Promising local artists are taken to see Jordan’s spectacular landscapes, in an annual art symposium organised by the National Gallery entitled Art & Nature.

Additionally, the Gallery runs an innovative initiative, the Touring Museum, which takes art to towns and villages in a van. I joined one such trip to Madaba, a town famous for its Byzantine and Umayyad mosaics. The programme’s long-time organiser, Suheil Baqaeen, laid out oil pastels and paper, and encouraged the classroom of eager youngsters to express whatever shapes and colours they fancied. It was a morning of smiles, pride, and enthusiasm, as the youth centre came alive with drawings of red buses, seascapes, and flags. Three original artworks from the National Gallery, chosen to inspire the children’s drawings, stood on easels in front of the class.

Building on Princess Wijdan’s dream of an international centre for Jordanian art, Mr Baqaeen has pursued his passion for democratising and popularising creativity. Alongside the Touring Museum, he has volunteered for many years at Jordan’s Royal Academy for the Blind, using scented paints to help the students imagine colour.

These initiatives are underpinned and fostered by the National Gallery, which is composed, in equal parts, of its artworks and its activities. Dr Khreis’ responsibilities lie as much within the sandstone buildings as without, inspiring and encouraging the next generation. And each day, busyness and artistry swirl around the sculpture garden, at the centre of it all.

If you enjoyed this article, you might also like:

11 Creative Platforms Celebrating Middle Eastern Arts And Culture

Leena Al Ayoobi – The Bahraini Artist Recreating The Image Of Women In The Gulf

Shift – 3 Female Saudi Artists Reflect On Their Changing Culture In A London Exhibition