By Katie Holland

As Ghada Samman’s headstrong heroine Zain discovers, winning her right to live as a free, independent woman entails answering to her own moral compass, fending off constant unsolicited judgement and, naturally, finding her way around a revolver. In this story of a young woman’s bold and noble quest for freedom, Samman weaves the joy and pain of liberation into an exuberant coming-of-age tale.

Samman’s novel, published in Arabic in 2014 and translated into English by Nancy Roberts (who also translated Samman’s Beirut 75 and Beirut Nightmares), is set in 1960s Damascus. While eminently a celebration of life and female emancipation, it also serves as a poignant reminder that the same rights and freedom of women around the world are still being fought over, or even facing a renewed threat from conservative forces. When the novel opens, Zain is living unhappily one year into a loveless marriage that she believed she wanted, having gone against familial and social pressures to marry a man of her father’s choice. Her first assertion of her independent nature has led not to the happiness she sought, but instead to suffocation, as Zain comes to realise that, in going from her sheltered family home to the restricted obligations of a wife, all she has done is to “trade one form of oppression for another.”

Samman’s novel, published in Arabic in 2014 and translated into English by Nancy Roberts (who also translated Samman’s Beirut 75 and Beirut Nightmares), is set in 1960s Damascus. While eminently a celebration of life and female emancipation, it also serves as a poignant reminder that the same rights and freedom of women around the world are still being fought over, or even facing a renewed threat from conservative forces. When the novel opens, Zain is living unhappily one year into a loveless marriage that she believed she wanted, having gone against familial and social pressures to marry a man of her father’s choice. Her first assertion of her independent nature has led not to the happiness she sought, but instead to suffocation, as Zain comes to realise that, in going from her sheltered family home to the restricted obligations of a wife, all she has done is to “trade one form of oppression for another.”

Moreover, she is pregnant. Zain’s successful mission to resolve this by having an abortion focalises the central theme of Samman’s book: the inevitable loss that accompanies freedom and the responsibilities one shoulders along the way. Beyond the fact that Zain’s journey to independence begins on the back of her abortion, which echoes her own birth that resulted in her mother’s death, this theme is captured through Zain’s awareness that death is a necessary facet of the (re)beginning of life. She states, “We have to go through a painful second birth” in order to be transformed into free and complete human beings. Zain visits her great aunt on her deathbed, whose mysterious final utterance is “Look . . . Look . . . What is it? Please . . . What is it?” Death is thus presented as a crossing into a new place of discovery.

For Zain, though, it is also a figurative way of leaving things behind in an act that fully embraces her agency. Of people whose values she rejects she says, “I kill them in my heart with a silent, bloodless elegance”; she leaves them in “my heart’s obituary column.” And yet her new-found freedom and agency lose Zain more than just underwhelming marital arrangements; as her actions inspire other young women to strike out against social norms, she loses her innocence and anonymity, and feels the responsibility to live up to others’ expectations of her, realising that her status as a radical single woman can only be realised through financial independence from her family.

Despite abandoning the “sinking ship” that was her marriage, Zain cannot escape the encroachment of Damascene public life into her private world. The extended family network and wider social circles are oppressively involved in the ‘scandal’ of her divorce, for which Zain is castigated and viewed with suspicion, while the surrounds of the city embody the incorrigible gossips living in its houses, who become its “talking windows.” In this way, Samman highlights how patriarchy is ‘built’ into the Syrian social fabric, and that, frustratingly, its restrictions are imposed on young women by their own female relatives. Seared into Zain’s memory is the image of a neighbour placing a hot coal on her daughter’s tongue after she asked if she, like Zain, could marry for love. Such a powerfully symbolic act of silencing women stands in stark contrast to Zain’s ability for self-expression.

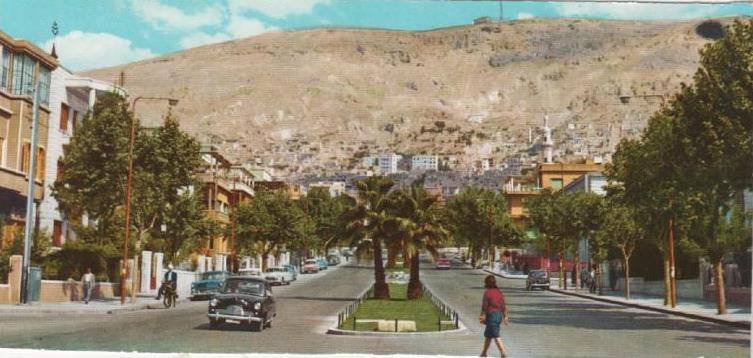

1960s Damascus (image: Twitter)

1960s Damascus (image: Twitter)

Zain lives to learn, think and write, and would prefer to dedicate her energies to these endeavours than to any man. As if this didn’t make her ‘dangerous’ enough, she gains recognition as a talented writer and is invited to participate at literary events. Zain’s inner authorial voice acts as her moral guide and support to her more doubtful outer self. This character split has a parallel in the narration, which alternates between characters’ inner voices and an exterior third-person perspective, with the former often serving as a vehicle for the voices of young female characters, like Zain’s cousin Fadila, who are not otherwise sanctioned to publicly express themselves.

However, it is not just women whose voices are stifled in Baathist Syria. The Baath Party’s suppression of free thought and insidious surveillance are evoked using surrealist images; Zain notices a man in a café sewing his mouth shut and observes ears growing out of the walls. The stultifying effect of the climate on Syrian citizens is implied when Zain denounces the corrupt doings of the regime, personified in the character of Lieutenant Nahi, to her fellow writer Alwan, whose only response to her outrage is to repeat, as though unable to critically receive the information, “you’re kidding.”

Through highlighting the importance of freedom of expression and the contribution of writers and thinkers, and by viewing women’s struggle for liberation through the lens of a courageous protagonist, Ghada Samman’s novel is inspiring to read against the backdrop of certain contemporary challenges: for women, the pursuit of our right to make our own choices (such as the recently successful pro-abortion campaigning in Ireland) and the continuing defence of that right (which has emerged as a potential issue in the US following the retirement of Justice Kennedy in June); and for society, remaining enriched by the work of writers and having access to the truth they are committed to seeking. In addition to these important reminders the novel provides us with, the greater significance of Farewell, Damascus lies perhaps in its emotive power as, in its uplifting tone, we are movingly presented with a state of happiness that highlights what is truly at stake in the pursuit of the free.

Through highlighting the importance of freedom of expression and the contribution of writers and thinkers, and by viewing women’s struggle for liberation through the lens of a courageous protagonist, Ghada Samman’s novel is inspiring to read against the backdrop of certain contemporary challenges: for women, the pursuit of our right to make our own choices (such as the recently successful pro-abortion campaigning in Ireland) and the continuing defence of that right (which has emerged as a potential issue in the US following the retirement of Justice Kennedy in June); and for society, remaining enriched by the work of writers and having access to the truth they are committed to seeking. In addition to these important reminders the novel provides us with, the greater significance of Farewell, Damascus lies perhaps in its emotive power as, in its uplifting tone, we are movingly presented with a state of happiness that highlights what is truly at stake in the pursuit of the free.

Buy Farewell Damascus on Amazon

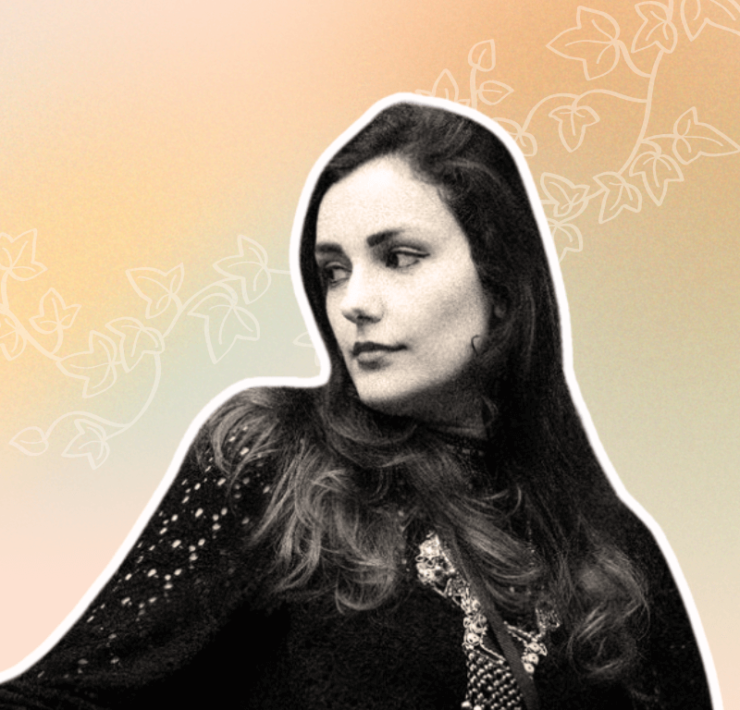

Katie Holland is an editor currently based in Cairo. Her undergraduate studies in Arabic and Persian have taken her to live, work and travel around the Middle East. She tweets as @katiejholland about literature, culture, politics and the environment.

Katie Holland is an editor currently based in Cairo. Her undergraduate studies in Arabic and Persian have taken her to live, work and travel around the Middle East. She tweets as @katiejholland about literature, culture, politics and the environment.

If you found this interesting, you might also like:

Iran’s City of Lies: Extraordinary tales of love, sex and death in Tehran

Mona Eltahawy: Leading the Middle East’s sexual revolution

5 Instagram accounts that show a different side to Syria

Driving While Female: Manal Al Sharif and the fight for women’s rights in Saudi Arabia

Very well written analysis/description of the book. At some points I felt as though I was reading the book myself & going through the emotions. Thank you & welcome to the team! I look forward to reading more of your work.

Thank you so much for your lovely comment! So glad you enjoyed it and I hope you’ll enjoy reading the book. 🙂